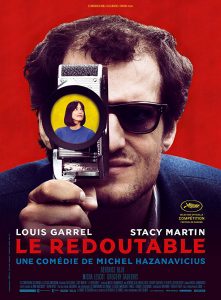

Nadia Bee talks to director Michel Hazanavicius about his latest film Redoubtable.

A cheerfully iconoclastic film, Michel Hazanavicius’s Redoubtable has provoked both ire and delight. Jean-Luc Godard is considered such a key figure in both European culture and political history that to treat him with levity is outrageous to some, and just deserts to others. Hazanavicius has said that critical responses have, at times, been as if he’d peed on the Sistine Chapel.

The late 1960s marked a turning point in Godard’s career as a filmmaker. He was already well-known for his brilliantly innovative approach to film form, and for his political engagement. He then took film form much further, with his 1967 film La Chinoise – an adaptation of Dostoyevsky’s novel The Possessed. It starred his then wife, Anne Wiazemsky. Wiazemsky had been Robert Bresson’s muse, and acted in his film – held by some to be the greatest film of all time – Au Hasard Balthazar (1966). While still very young, she was already a person of note in France, in her own right.

A well-known novelist, she published Un An Après, an account of her life with Godard, just two years before her death in 2015. She had systematically refused to grant anyone film rights, until Hazanavicius called her. She initially turned him down, but just before she hung up her phone, he told her it was a pity, because the book was so funny. Hazanavicius is deeply influenced by the Italian tragi-comedies of the 1960s and 1970s, by filmmakers such as Dino Risi, Mario Monicelli, and Ettore Scola. He says the best example of such films is Dino Risi’s 1976 film Una Vita Difficile. Wiazemsky was struck by his insight, and changed her mind. The result is a film which is both hilarious and deeply moving, and which also, somehow, offers a fresh perspective on the events of May ’68.

When I met Michel Hazanavicius in London, his warmth and enthusiasm were striking, as was his respect for Wiazemski. He noted how, in writing Un An Après, Wiazemski had remained true to the young woman she had been in the late 1960s. He also remarked that it was a time when women did not quite have their rightful place in political and intellectual discourse. Redoubtable is a sharp, but witty and generous insight into what it must have been like for a bright young woman to live with a celebrated, perpetually striving, dissatisfied, self-absorbed man. Un An Après offers a much-needed narrative for those times.

It seems counter-intuitive that a film director known for comedy and for something which at times borders on pastiche, should choose to make a film about Jean-Luc Godard – so this was of course the first question I asked Hazanavicius when we met.

NB: What drove you to make a film about Jean-Luc Godard?

MH: The book. I had no will to make a movie about him. I have a very relaxed relationship with Godard. I don’t adore him, I don’t hate him. I have a very classical relationship to his cinema. I think his movies from the Sixties were very, very good, and charming and seducing. And after, I lost (track) a little bit. I don’t really follow him, but I respected. There was no reason for me to make a movie about him. And when I read the book, it’s a bit thanks to the book that I discovered that love story – very sad, very original as well. Because it’s not a love story ending because of sexual reasons, or lack of love. It’s really for political and artistic reasons, so I thought it was very original and I felt that I could tell that story in a fun way. And I think it’s the perfect balance. That’s what the Italian comedies did so well. The balance between drama and fun.

NB: Do you feel you’ve now altered the perspective of the French public about the 1960s? There’s been a cult of Godard – austere – but here everything seems to break into technicolour.

MH: Well, the people who saw the movie, they really enjoyed it, they loved the recreation of it, you know, May ‘68 is iconic, and Jean-Luc Godard is iconic as well – but not in the same way. Jean-Luc Godard – it’s a sharp subject. So, many people do not feel concerned by his life and his topics. But May ‘68 really changed the way we lived in France. May ‘68 really freed the country, and school was different, sexuality was different, the politics were different after that, and really, it changed the way people live. So, yeah, there was something really fresh about ‘68. And from what I know, there isn’t a film that really recreated May ‘68 the way it is in the movie. It’s always been in a serious way, first, and it’s the idea, what we think of May ‘68, was really funny, the slogans were really funny. When you see images of Daniel Cohn-Bendit (note: a key student leader during May ’68, now a politician), he was always smiling, there was something arrogant but in a really cool way, in front of the police. I tried to recreate that very specific energy.

Godard and Wiazemsky married in 1967, but by May 1968 Godard’s personality seemed to be rapidly changing, and the marriage was becoming difficult – by 1970 the relationship had ended, though they only divorced in 1979. It’s a story which seems at some levels to echo Godard’s 1963 film Le Mépris (Contempt) – which was based in turn on Alberto Moravia’s 1954 novel Il Disprezzo.

NB: How much did Le Mépris influence your perspective of the breakdown of the marriage in Le Redoutable?

MH: It was not so conscious. But doing it, of course I realised it was the same movement, of a woman looking at her husband going further and further from herself, and at the end she had no other choice than not loving him anymore, or realising that she doesn’t love him anymore. But I didn’t try to make it look like Le Mépris. The only thing, when they went to, that’s in the book, when they went to the South of France, and when he’s going to Cannes, I tried to find not the same house but the same kind of mood. But once again, I watched of course the old Jean-Luc Godard movies, and especially the ones from the Sixties, when I was writing, but then I stopped doing it because my idea was not to recreate exactly, but more to work at the memories in the book.

NB: I really felt that, as you say. Also, what your film made me realise – and I could be wrong – but that Godard was in fact aware that he was replaying a previous disaster in his life, and so that gave me a much warmer perspective on the man.

MH: Yes, for many people, there’s, let’s say three kinds of people, three kinds of relating to Godard. The ones who adore him – you can’t say anything that could put him down from his pedestal; the other ones are the ones who hate him, because they think he is a snobbish, non-interesting crook, and intellectual-but-we-don’t-understand what… But for the main part, people don’t know him, or they don’t care.

For the ones who adore him, I did something really wrong, I made fun of him. But for the ones who hate him, or the ones who don’t care, I think I humanised him. I think we look at him in a humane way, we understand, because I think it’s the most important fracture in his life, this part. There were many fractures, before, when he breaks with Anna Karina for example. But this one is very important because he really started to change all the perspectives of his life, artistic and also with his friends, also his couple (relationship), and with himself. So it’s a very important fracture. And when we understand the reasons for that fracture, that makes him very different. You look at him in a very different way. And for a lot of people he has been humanised, so I think it’s good for him, at the end.

NB: When you constructed the character of Godard with Louis Garrel, what kind of process was it? You must have started from different points of departure, because everyone has a different idea of a person, and yet it is so coherent.

MH: Yeah but when we started to work with Louis, there was a script. So, for me, there were many steps along the way. I worked alone on the script, that was one thing, and it was very important too. Anyway, during all the process, my point was to find the right balance between irony, between the positive and between the negative. So for example, making a movie with ‘bad’ form. The form of the film is a real homage to Jean-Luc Godard’s work. So I thought that in doing all these positive things for him, I could be more ironic in the story. And also, because the story – he was an asshole, also. Not just an asshole: he acts sometimes as an asshole, so I had to include it. He never tried to be sympathetic – so it’s not a betrayal to show him in that kind of situation.

Anyway, I humanised him, even when he is really mean, he’s not mean just to be mean. He’s mean because he is pursuing a very high goal for him, which is a sort of truth, or something, and so it’s not just a mean person. I don’t tell the story of an asshole. Still, in some sequences, he looks ridiculous – so I have to find the right balance.

When I was writing the script, I had that part which forms a homage, but also I try to respect him as a human being and to put in all this destruction – because he has a sense of destruction. He destroys a lot of things around him. But at the end, he destroys himself, and tries to commit suicide. You realise he is his own victim. If he destroys things to protect himself, he is a pure asshole. That’s not his case. He is doing it because he cannot do anything else but be a victim. Being a victim, I thought we would have some empathy for him.

And when we started to work with Louis, this work was behind us. He adores Godard, he is a huge fan. I realised quickly he wouldn’t go towards something ridiculous, that would be bad for Godard. I tried to push him a little bit towards comedy, and he is not used to comedy. So he was a bit insecure. He usually said, I trust you for comedy. Funny, for example he did funny things, but saying “ah I don’t have vis comica”, which is a Latin word for funny, which is very funny, because no one uses that kind of word. But he can be very funny. It was really a great experience to work with him, he is very talented and very funny.

The highlights of the film, both comic and bittersweet, include the fights Godard picks up with his friends and allies. These disruptive moments seem to come out of nowhere, and yet appear utterly inevitable. One of these moments is a delight, and seems hardly true: a bust-up between Bernardo Bertolucci and Godard, one night in a piazza in Rome. But it really did happen, and Bertolucci even spoke about it with Louis Garrel. But destructiveness in Godard coexists with prolific inventiveness. Hazanavicius points out that Godard is always doing something new.

NB: And for you? What’s next?

MH: Oh, I am not a revolutionary. I am much more simple, much more classical. I love comedies. I hope it will be a comedy. I am working with a French producer, Philippe Rousselet. He has sent me a very good script. It’s a comedy, very original. I really hope that it will be my next movie.